THE FLARE PLAYERS AND TV VIOLENCE

By Nicholas Hughes

April 11th 1969.

Hog waits for Spicer to show his big, ugly mug at the nightclub. He waits in the shadows, holding bottle of clear liquid that clearly isn’t water…if you know Hog. Spicer arrives in a flash, white car, his moll right beside him. Hog steps out from the shadows but Spicer isn’t intimidated; this young upstart knows nothing about how to run a gang. He confronts Hog, telling him precisely what he thinks of him and gives him a slap. Hog has his answer ready, he’s been waiting for this moment…the moment to bring Spicer down.

“You’re never too old to learn……and NOBODY hits Hog!”

Hog sneers at the older man and, quick as a flash, throws the contents of the bottle right in Spicer’s face. Spicer grabs his eyes and screams. His flesh is burning: Hog’s thrown acid right into his face. The moll screams in shock, Hog throws a bit more, and again, smiling, sneering. Spicer is doubled over, screaming in agony as the acid sears his skin and blinds him.

….meanwhile, thousands of viewers are now making their way to their telephones to complain to ITV about this new crime show.

This was the climax of the first episode of ITVs evening crime drama, “Big Breadwinner Hog” starring Peter Egan. Throughout the show, the viewers were introduced to some of the most unpleasant and ruthless criminal characters that had graced British TV screens up to that point. When, earlier on, Spicer beat up Hog the director chose to show it with a series of extreme close ups of Hog getting repeatedly hit in the stomach. Even that scene was considered extreme and yet things went overboard for the acid attack at the end. The programme makers knew what they were doing: Big Breadwinner Hog was meant to be a violent, aggressive show pitching the old criminal world with that of the young 60s mod culture. When submitting a synopsis of the show to the ITV chiefs, they played down the violence by referring to the fight scenes as “a fracas ensues”.

The backlash against the show, once that first episode was shown, was extremely vocal and immediate. The phone lines were jammed with complaints and the show was pushed into late night slots (or in some regions, not shown at all). But the ratings were still pretty good…

11th April 1969 is a watershed moment in the depiction of violence on British television screens. Throughout the Sixties the fight scene had become a staple of TV drama through its wide use in the glossy Lew Grade action shows and the daring ideas of writers and producers in that decade led to the boundaries being pushed back further and further in an era when everything seemed ripe for experimentation. Now, in “Big Breadwinner Hog”, there was a show doing both. The arguments raged about how appropriate it was to depict such acts and the vile characters carrying them out. What was lost in these arguments was the fact that it was a character played by the young Peter Egan carrying out most of them.

People normally associate Egan with cheery, laconically charismatic sitcom characters: The romantic older man who will sweep your wife off her feet. In 1969 he was 23 years old and starring in only his second TV series, and securing the lead at that. It is fitting that the most violent act in British TV drama in the 1960s was carried out by a young actor, one of the Flare Players, because youth and aggression were soon to dominate the cultural landscape. 1968 was dubbed the Year of Revolution because of all the anti-war, race and student riots breaking out all over the world. From the Chicago Democrat Convention, the Left Bank riots in Paris and the anti-Vietnam war protests the world over the peaceful flower children of 1967 moved aside, or got swept up in, the anti-establishment movements a year later. Within short order football hooligans in the UK and the rise of the Red Brigades and Baader-Meinhoff gang made people even more worried about violent youth turning on their elders than when teen violence kicked off back in the 1950s. Now, young people had bombs and degrees.

British TV were quick to capitalise on this and looking at the Lew Grade ITC staples of the Sixties, it is the younger kind of criminal (or heroic) character who often steals the show. Ian Ogilvy, for example, made for a particularly dashing hero in an episode of The Avengers; managing to woo Linda Thorson and sweep aside Patrick MacNee in one fell swoop. In the latter episodes of “The Prisoner”, Alexis Kanner practically blows away everyone else on screen. Peter Egan aside, if you wanted an actor to be cast as a nasty, up and coming and smart dressed villain then producers went for Michael Gothard. If you wanted slimy and desperate, Ronald Lacey was the choice du jour. So many of the Flare Players had an edginess to their performances, whether it was being icy cold and ruthless or else a manic unpredictability. Some, like Ogilvy, would launch a massive charm offensive on the viewer. Sure, if you were producing an action TV series in Britain in the Sixties and Seventies, you always had the reliables to cast in your shows: Dudley Sutton, Lee Montague or David Hodge but for a bit of danger, try adding John Castle to your show, retire to a safe distance and watch what happens.

After Big Breadwinner Hog departed from British TV screens rather ignominiously, there were many things to ponder. That the show went too far with completely unsympathetic villains meting out extreme violence on one another was not up for question. It was a matter of what to do next, now the genie’s out of the bottle so to speak. Hog was getting good ratings when it was shown in regions that didn’t shove it in the backwater time slots. Egan proved a charismatic young actor for the future and a bit of aggro and rough stuff was alright, as long as it didn’t extend to people having their faces melted with acid whilst the camera lingered on it. The new wave of police and action thrillers on TV would be influenced not only from the Hog experience, but from other sources.

In the main, TV took its lead from the cinema. A whole slew of up and coming actors got to wreak havoc in Lindsay Anderson’s “If” but not much of that could translate into prime time TV drama. What did was the new wave of crime thriller, centred around the police procedural, being made. Movies such as “Bullitt”, “Madigan” and, quintessentially, “Dirty Harry” would shape the way British TV action and violence would be portrayed on our screens. You could have villains like Hog, but what was needed was a law enforcing counterpart to balance him out.

The Lew Grade blueprint of the Sixties was a sound foundation for what followed. Shot on glossy colour film with lots of guns being pointed and fired and plenty of knock-down fist fights, the ITC action dramas were tightly paced and efficient entertainment but they often had unlikely protagonists and villains or some other kind of weird set up from elite Interpol agents, disgraced CIA operatives and a private dick and his ghost buddy. Regular police procedural dramas of the sixties tended to be heavy on dialogue and character and light on action. What was needed was the action of the former matched to the more down to earth set up of the latter.

Enter Euston Films.

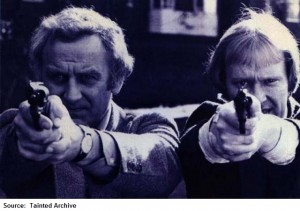

Set up by three Thames TV executives, Euston Films knew exactly where to take the British television action drama: Onto the mean streets of the city and shot on glossy film stock. The style would be uncompromising; the intensity and the aggression of the crooks would be matched by even more intensity and aggression of the police protagonists. The first thing they did was to take an existing ITV crime drama called “Special Branch”, which at that time was shot in a mix of studio-bound videotape and location film stock, and shot it entirely on 16mm film. Along with the change in style, there was a big change of cast. Out went the flamboyant Derren Nesbitt and in came George Sewell, an actor seemingly carved out of the East End of London. It was a shrewd move; whilst Nesbitt could ooze charm or creepiness as required and was already a familiar face to British viewers, Sewell had an authenticity about his performances borne of real life experience growing up in the East End and having stints in the merchant navy. He was also firmly identified with filmed action roles, from the seminal British gangster film “Robbery” to TV action shows such as “UFO”. The new Special Branch was almost entirely action-driven with the fight scenes and use of firearms upped in terms of quantity and realism. As the producers put it: “Kick, bollock & scramble”.

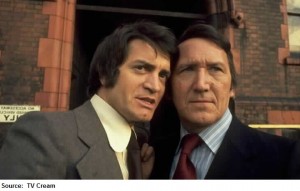

With the new style introduced, Euston Films wanted to go one better. In 1974 they launched their benchmark TV show: The Sweeney. Along with the more brutal style of Special Branch, the two leads cast were somewhat younger than TV audiences were perhaps used to. It’s a little hard to believe that John Thaw was only 33 when he first played Detective Inspector Jack Regan. Thaw always looked about 10 years older than he was and considerably more grizzled and moody than any TV cop before him. Fresh faced and youthful Dennis Waterman was, at 25, a very young leading actor cast in a major cop drama but the producers wisely decided not to make him a naïve and callow youth under the tutelage of the wise old master, Regan. No, instead they made Detective Sergeant George Carter as rough and brutal as his boss: Capable of boozing all night, fighting all day and eyeing up as much talent as the most lecherous middle aged rozzer.

The show was an instant hit and raised the violence levels up a couple of notches further still, enough to match Dirty Harry’s brutality. The punch to the gut and the knee in the groin were The Sweeney’s groovy moves and now British coppers routinely carried and fired guns. Older, reliable actors got some good villain parts but the more memorable guest roles went to the younger, more explosive kind of actors emerging in this era; our Flare Players. Hywell Bennett made an engaging nebulous son of a crime boss, promising to go straight whilst playing everyone around him off each other (and winning). Pop star Paul Jones cropped up as a leery young villain, George Sweeney made for perhaps the show’s most dangerous psychopath the Flying Squad had to deal with, 70s stalwarts Del Henney, Keith Buckley and Tony Anholt were there and even George Layton managed a memorable turn as an Australian armed robber. Whilst this was all going on, PC George Dixon of Dock Hill quietly retired.

Euston Films produced some equally nasty and violent stablemates with Van Der Valk (like The Sweeney, only in Holland) and “Frank Ross is OUT” which gave the incendiary performer Tom Bell his signature role as a released convict on a quest for vengeance. And where there’s Tom Bell chasing the scum that sent him down, Derrick O’Connor isn’t far away. Euston Films trajectory then took them to the crime family drama “Fox”, with Derrick O’Connor again, Ray Winstone and Larry Lamb among the cast which had similarities to The Sopranos in its set up but done with that British propensity to kick someone in the balls in the name of prime time drama. By the end of the 70s, Euston had one more trick up its sleeve; a show that took some of the ingredients of their previous shows and filtered it through a comedy lens: Minder. Dennis Waterman was in his prime at 31 and a lot of the style and faces from Euston’s other productions again crop up here. By 1983, the glory years of Euston’s brand of gritty violent drama came to an end with the female led “Widows” which had that Euston signature but this time featuring a female cast: Previously women in Euston Films were relegated to bumped off girlfriend of the week or else gangster’s molls. By this stage, tellingly, most of the best known Flare Players (male and female) weren’t involved in this production. A new generation of actors and actresses were emerging.

In between The Sweeney and Minder another ITV production team were jumping headfirst into the brutal style of TV action drama. Albert Fennell and Brian Clements had steered The Avengers during its peak years and were back, in 1976, to launch the show again in The New Avengers. There were to be a few changes to the format; now John Steed had two assistants, the obligatory glamorous but dangerous girl, Purdey (Joanna Lumley) and a beefcake younger action man, Gambit (Gareth Hunt). There were worries that Steed might be pushed to the background as a mentor figure to make way for Gambit’s front line investigative and resolution work but it was genuinely a 3 way show. Hunt’s presence made sense: Steed’s sword cane, tricks with bowler hats and debonair style clashed with the new kind of crime dramas being made in the mid-Seventies so having a regular character who would be more credible punching someone in the face over and over was a smart move. And this freed Patrick MacNee from having awkward romantic scenes with the 29 year old Joanna Lumley so the “will they or won’t they?” dynamic shifted to Hunt and Lumley.

At the time, The New Avengers didn’t quite hit the mark despite being fairly well liked. The Avengers was a heavily stylised world of mad scientists and moustache twirling villains. Even though The New Avengers tried to move those concepts into the seventies, it was still a bit too weird and out there to fit in with the kinds of action dramas (now bolstered by American imports Starsky & Hutch and Kojak) being made. Clements and Fennell started work on a new show: One that would keep their trademark showmanship intact but would deliver what The Sweeney couldn’t: excite boys aged 8-16.

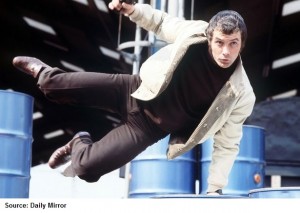

The result was the most beloved of all action crime dramas: The Professionals. The show literally began with a car driving through a window and never let up from there. At its core were two young actors who came from very different performing backgrounds (Shakespearean theatre and music and comedy) to become pin ups, action heroes, housewives’ favourites and the stuff of boyhood adventure. Martin Shaw and Lewis Collins threw themselves into their roles, I mean, LITERALLY threw themselves. Fennell and Clements glossy production touches merged seamlessly with the more down to earth crime drama format. Directors (and even actors) moved from The Sweeney into The Professionals without missing a beat. There was a clever little trick in the show’s format where CI5 was a law enforcement agency, but with military overtones which allowed a certain amount of crossing over between police and army (embodied by the characters). So the villains in a lock up would have access to advanced battle rifles, for example. This was all the stuff boys growing up in the era fed on. The physicality of Shaw and Lewis certainly helped the show and even led to Lewis Collins taking a leaf out of his character’s book by taking up skydiving and joining the Territorial Army. One Flare Player who stole the show was John Castle, playing a maverick CI5 agent called Tommy. Castle, no stranger to stealing scenes, showed that on his own he could ride a speedboat and fire a rifle grenade at the same time. You almost wished he’d become a cast regular and anyone who has seen the episode rates it as one of the best.

Castle was also in I, Claudius, a show that didn’t let its studio bound format get in the way of some serious and violent nastiness. In many ways, scenes in the show were more shocking than Hog’s acid attack but by using strategically placed cuts, implications in the script and heeding Caligula’s advice to “don’t….go in there”, the viewer was spared much gore although swords rammed through the stomach were a common sight. The show was the greatest assembling of Flare Players on screen and most of them get to do the most violent and graphic death scenes: Ian Ogilvy (poisoned), John Castle (stabbed, then thrown from a tower), David Robb (poisoned), John Hurt (multiple stabbings), Simon McCorkindale (beheading), the list goes on.

The Professionals is the high water mark of British TV action drama and lasted for 4 series. The old Lew Grade action shows still had some life in them by this stage with Space: 1999 and The Return of the Saint. The former regularly featured punch ups and laser battles that characterised Star Trek in its original run and supporting the two middle aged American leads were a bevvy of Flare Players such as Tony Anholt, Prentiss Hancock and honourary Flare Players such as the antipodeans Nick Tate and James Laurenson. These guys were meant to be the ones throwing their weight around in fight scenes and at times it looked like Anholt and Tate were running away with the show from the ostensible leads. The Return of the Saint was a high water mark for Ian Ogilvy, who effortlessly played the role of Simon Templar with aplomb. The show had the gloss and finesse of Grade’s earlier show, The Persuaders, with all of Ogilvy’s charm and wit on display whilst the action was firmly in the classic Grade mould: Expert fight choreography at regular intervals and a bit of shooting but stopping short of doing the kind of stuff Regan, Carter, Bodie and Doyle were doing.

By 1979 Grade was moving into movie production and there was just a slight sense the mood was changing in TV production. It’s at this point we must introduce a conspicuous absentee from this story. He’s an actor who became synonymous with British TV action drama of the Seventies. A true icon who defined the era and who’s work crossed over into all the shows I’ve described so far and many more besides.

Patrick Mower

Mower left a trail of wrecked cars, explosions, beaten up suspects and wholesale destruction over the course of the 1970s. Just looking at his roles from 1969 onwards shows you what an impact (literally) he made on almost every British TV show made in that era: From “Callan”, playing the yang to Callan’s ying in James Cross, “Special Branch” as Haggerty the upstart younger partner to George Sewell’s grizzled inspector, “The Sweeny” playing a memorable Australian armed robber with an appalling accent, the usual Lew Grade ITC action shows and a regular panellist on the ITV game show “Whodunnit”, where a panel of celebs had to work out who was the murderer in a little play shown to them. You half expected Mower to leap up from behind his desk and beat a confession out of one of the suspects.

So when the BBC decided to do things the Euston films way and make their own belated version of The Sweeney or The Professionals with “Target”, there was only one actor they could realistically turn to: Patrick Mower. His rugged charm, incendiary TV screen presence and macho physicality was just right for the part of maverick cop, Hackett. Target was produced by Phillip Hinchcliffe, a former Dr Who producer who got into trouble with Mary Whitehouse over the amount of violence he brought into that show. So, let’s recap here: The BBC want to make an action TV cop show, they hand the keys to the project to the man who made Dr Who more violent and nasty (but brilliant at the same time) and in turn they cast Patrick Mower in the lead. How could they have been shocked and surprised by what happened next?

Target became more action packed, aggressive and nastier in tone than Special Branch, The Sweeney and The Professionals that preceded it. Fist fights resulted in more gore, the villains were more ruthless and Hackett was a nasty piece of work who had a notoriously short fuse as he beat down suspects, wrecked cars like there was no tomorrow and instilled a culture of fear within his team. It was magnificent stuff with Mower reigning supreme in a playground that seemed specifically designed for him. However, it was too much for some people. The media press hated it, the public were shocked and, in scenes reminiscent of the Big Breadwinner Hog episode, some disgruntled viewers got onto the complaint hotlines and Mary Whitehouse’s National Viewers and Listeners Association sharpened their already razor sharp knives. The BBC were unsure about what they had unleased onto the world; after all, wasn’t Target the kind of show the British public were craving? Maybe so, but times were starting to change and for every fan of the show, there was another who felt moved to complain.

Media history is full of revisionists and you’ll find a great example of this when it comes to talking about Target. The new, semi-official line is that Target is an un-redeeming nasty show with no charm which was a failure, led to a huge falling out within BBC drama and that the show should never be repeated ever again. The truth is somewhat different: Target was enough of a hit show to warrant two series and a series of adverts featuring Patrick Mower and Brendan Price in their Hackett and Bonny personas. Looking at it from some distance, the show is totally in keeping with the kind of crime dramas that had been made across the decade, both film and TV. There was nothing particularly original about the set-up, if you were familiar with The Sweeney and The Professionals, but it was more no-nonsense without the flippant banter of two lead actors. It was Mower’s show and a lot of the drama came from his rage filled performance. So it held its own as an action crime drama, but certainly divided critics and audiences and after two series things came to an, end: Target, action dramas and a lot of careers as leading men.

By 1980, things were winding down in action TV. Minder was entering a second season; it had the look and feel of The Sweeney but the action and violence was replaced with banter and comedy. Waterman could still do the fight scenes, if required, but the show rationed them. Target was off the air for good, The Sweeney long since gone and The Professionals about to enter its swan song. New TV programmes came along that bore no relation to the action shows of the previous two decades. Where once “I Claudius” was hailed as the greatest TV drama ever made, in 1981 it was shoved aside by “Brideshead Revisited”. It’s star, Anthony Andrews, was once considered for the part of Bodie in The Professionals and his last big gig was defusing unexploded Luftwaffe bombs in Danger: UXB. Now, he would carry nothing more dangerous than a teddy bear.

As the Eighties progressed, the action drama died bit by bit. Sure, there was a late flourish with “Dempsey & Makepeace” which played around with the buddy cop formula by having one of them a woman but it didn’t have the nasty edginess of its predecessors. By 1987 the nail was in the coffin with the arrival of Inspector Morse; now we had the sight of John Thaw having to solve crimes sitting down in a pub and musing theories to his sidekick for two hours before the murderer eventually confesses and explains the plot. It was a huge hit and the indicator for most British crime drama shows from now on. Another show, “Between the Lines”, turned on the police force and showed the entire institution as irredeemably corrupt. Violence was replaced with sex as the lead character bedded his co-stars whilst decrying corruption. There were some half-baked attempts at reviving action drama; the 1980s version of The Saint has almost been forgotten, Saracen was a pale copy of The Professionals, as was CI5: The New Professionals and even the critically panned “Civvies” showed that British TV directors had no idea how to depict gangsters or choreograph a fight scene anymore.

Focus was, again, on the shows themselves but something had been overlooked: The actors. Was it purely a matter of revulsion of TV violence that kept viewers away from these newer shows? Was it that British TV had truly lost the ability to do action anymore? Or was it that the cast lacked the ability to reach out and grab the viewer by the jugular? For what marked out the age of TV action were charismatic and dynamic actors who threw themselves into the show and could charm you whilst punching someone in the stomach 10 times. The cocksure glint in Peter Egan’s eye, the brooding malevolence of John Thaw, the fresh faced thuggery of Dennis Waterman, the sex appeal of Bodie and Doyle, the debonair swagger of Ian Ogilvy, the intensity of the cast of I, Claudius and the all round mayhem with a sly grin that Patrick Mower had in bucketfuls. It was the Flare Players that made British TV action so memorable and lacking that panache, the successor shows couldn’t win the hearts of the viewers.